Coert Visser, 2010

The Relationship between Equality and Thriving

The Relationship between Equality and Thriving

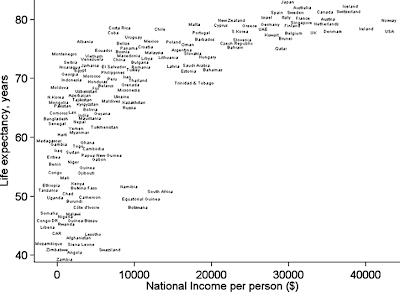

Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, two English epidemiologists, have written The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger , a provocative book on how high levels of inequality in societies is harmful for everyone within them. Their research shows that while economic policies in developed countries stress the importance of economic growth, economic growth is mainly an important determinant of the degree to which societies thrive. After a certain point the contribution of further economic growth begins to create only diminishing marginal returns: the relationship between economic growth and certain objectively measurable outcomes, like life expectancy, level off (see figure 1).

, a provocative book on how high levels of inequality in societies is harmful for everyone within them. Their research shows that while economic policies in developed countries stress the importance of economic growth, economic growth is mainly an important determinant of the degree to which societies thrive. After a certain point the contribution of further economic growth begins to create only diminishing marginal returns: the relationship between economic growth and certain objectively measurable outcomes, like life expectancy, level off (see figure 1).

Source: Wilkinson & Pickett, The Spirit Level (2009)

In developed countries, national income per person and economic growth are not the most important predictors of societal thriving but the level of equality. Wilkinson and Pickett’s research shows that many health-related and social problems are associated with the level of inequality of society. Here is how they did their research. They gathered data from 23 of the richest countries in the world from the World Bank and gathered internationally comparable data on the following health and social problems: level of trust, mental illness (including drug and alcohol addiction), life expectancy and infant mortality, obesity, children’s educational performance, teenage births, homicides, imprisonment rates, and social mobility. Here is an example of a graph, showing how an index of these measures is related to income inequality.

Source: Wilkinson & Pickett, The Spirit Level (2009)

To test and cross-validate their findings, the researchers tested these findings in a new data sample which consisted of the 50 American states. This research confirmed their findings across nations which adds to the credibility of the claims. Below is a graph showing how the index of health and social problems is related to income inequality in US States.

Source: Wilkinson & Pickett, The Spirit Level (2009)

The book contains many more graphs showing specific relationships between income inequality and separate measures of societal functioning (see these slides).

Why is this relevant for positive psychology?

Positive psychologists have done much research into how money is associated with happiness and some of their findings, at first glance, seem to be at odds with Wilkinson and Pickett’s findings. Berg and Veenhoven (2010), for instance, found little relationship between income inequality and average happiness in nations. It seems paradoxical that income equality would be related to many objectively measurable problems but hardly at all with happiness. How can one be equally happy when objectively things are worse? What is going on here?

This question takes us back to the original formulation of positive psychology’s mission. Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (2000) wrote: “We believe that a psychology of positive human functioning will arise that achieves a scientific understanding and effective interventions to build thriving in individuals, families, and communities.” This wonderful definition allows for research to identify any type of determinant of thriving to be found, like personal, motivational, habitual, or situational.

In practice, however, positive psychology is usually more narrowly operationalized. For instance, on the Wikipedia page of February 15, 2010, it is defined as follows: “Positive psychology is a recent branch of psychology that studies the strengths and virtues that enable individuals and communities to thrive”. This definition mentions only strengths and virtues as candidates for causal factors of thriving and it makes no mention at all of contextual, situational or structural factors affecting thriving.

A broader perspective on thriving and its determinants

As psychologists, we have known for a long time how important situational factors are in influencing our perceptions, beliefs, behaviors, feelings, and performance. Wilkinson and Pickett’s research is another example of this and it fits splendidly within the original definition of positive psychology in the sense that it contributes to the scientific understanding of how communities and its members thrive.

Also, it is an illustration of the limitations of using subjective criterion measures in research. Apparently, we can report well-being while objectively things are not going too well, both on an individual level and on a society level. We should not equate thriving or flourishing with subjective well-being. On this Barbara Fredrickson, author of Positivity, writes: “Flourishing goes beyond happiness, or satisfaction with life. True, people who flourish are happy. But that's not the half of it. Beyond feeling good, they're also doing good -adding value to the world. People who flourish are highly engaged with their families, work, and communities. They're driven by a sense of purpose: they know why they get up in the morning.’

For positive psychology to thrive, it needs to move beyond a somewhat narrow focus on happiness and strengths and take into account a broader perspective on thriving and its determinants.

References

- Berg, M. & Veenhoven, R. (2010). Income inequality and happiness in 119 nations. In search for an optimum that does not appear to exist. In: BentGreve (Ed.) ‘Social Policy and Happiness in Europe’, Edgar Elgar (in press)

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2009). Positivity. Groundbreaking Research Reveals How to Embrace the Hidden Strength of Positive Emotions, Overcome Negativity, and Thrive. New York: Crown Publishers.

- Pickett, K. (2010). Why Inequality is bad for your health. http://bigthink.com/ideas/18463

- Seligman, M.E.P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive Psychology. An Introduction. American Psychologist. Vol 55. No. 1. 5 14

- Wilkinson, R. & Pickett, K. (2009). The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger

. New York, Bloomsbury Press.