By Coert Visser

Wallace Gingerich is Professor Emeritus of Social Work at the Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio. As a core member of the Brief Family Therapy Center in Milwaukee (BFTC), Wisconsin, in the 1980s, he has been an important contributor to the development of the solution-focused approach. In this interview, he looks back on how and why he joined BFCT and on how the solution-focused approach emerged in the next few years after he joined. Also, he talks about the BRIEFER project and about a soon to be published review of the research on the effectiveness of the solution-focused approach. Finally, he reflects on the ways the solution-focused approach may further develop.

Read the full article »

Tuesday, September 28, 2010

Friday, May 14, 2010

Whistling Vivaldi And Other Clues to How Stereotypes Affect Us (Book Review)

BOOK REVIEW: Steele, C.M. (2010). Whistling Vivaldi: And Other Clues to How Stereotypes Affect Us (Issues of Our Time). New York, W.W. Norton & Company.

By Coert Visser

This review was first published on Positive Psychology News Daily

By Coert Visser

This review was first published on Positive Psychology News Daily

This book by social psychologist and Columbia University provost, Claude Steele, is a splendid example of how psychologists can make valuable contributions to society. In the book, Steele writes about the work he and his colleagues have done on a phenomenon called stereotype threat, the tendency to expect, perceive, and be influenced by negative stereotypes about one’s social category, such as one’s age, sex, sexual orientation, ethnicity, profession, nationality, political affiliation, mental health status, and so on.

Experiments demonstrating the impact of stereotype threat

When trying to understand certain performance gaps between groups, Steele and his colleagues did not focus on internal psychological factors.. Instead, they tried to understand the possible causal role of identity contingencies, the things you have to deal with in a situation because you have a given social identity. Over the years they carried out a series of creative experiments* in which there was a control condition in which a task was given under normal life conditions. In the experimental condition, the identity contingency was either cleverly removed or it was deliberately induced. Here are three examples of experiments to clarify how they worked.

Experiment 1: Steele and Aronson (1995)

In this experiment the researchers had African American and white college students take a very challenging standardized test. In the control condition, the test was presented as these tests are always presented – as a measure of intellectual ability. This condition contained the stereotype that African Americans would be less intelligent. In the experimental condition the test was presented in a non-evaluative way. The test takers were told that the researchers were not interested in measuring their ability with the test but that they just wanted to use the test to examine the psychology of verbal problem solving. In the control condition, the African American test takers, on average, scored much lower than the white test takers. For the white test takers there was no difference in their scores between the control condition and the experimental condition. For the African American test takers there was a big difference between the control condition and the experimental condition. They solved about twice as many problems on the test in the experimental condition. Moreover, there was no difference between the performance of the black test takers and the white test takers.

Experiment 2: Aronson, Lustina, Good, Keough, Steele & Brown (1999)

In this experiment, the researchers asked highly competent white males to take a difficult math test. In the control condition the test was taken normally. In the experimental condition, the researchers told the test takers that one of their reasons for doing the research was to understand why Asians seemed to perform better on these tests. Thus, they artificially created a stereotype threat. In the experimental condition, the test takers solved significantly fewer of the problems on the test and felt less confident about their performance.

Experiment 3: Shih, Pittinsky & Ambady (1999)

In this experiment, a difficult math test was given to Asian women under three conditions. In condition one, they were subtly reminded of their Asian identity, in condition 2 they were subtly reminded of their female identity. In the control condition they were not reminded of their identity. The women reminded of their Asianness performed better than the control group, whereas those reminded of their female identity performed worse than the control group.

How does stereotype threat harm performance?

Today, research on stereotype threat effects is done throughout the world by many researchers. Much insight has been gained into what it is and how it works. Briefly, you know your group identity and you know how society views it. You are aware that you are doing a task for which that view is relevant. You know, at some level, that you are in a predicament: your performance could confirm a bad view of your group and of yourself as a member of that group. You may not consciously feel anxious but your blood pressure rises and you begin to sweat. Your thinking changes. Your mind starts to race: you become vigilant to all things relevant to the threat and to what your chances of avoiding it are. The book title comes from an observed behavior: an African American whistling Vivaldi to make clear that certain stereotypes attached to the group don’t apply. You get some self-doubts and start to worry about how warranted the stereotype may be. You start to constantly monitor how well you are doing. You try hard to suppress threatening thoughts about not doing well or about the negative consequences of possibly failing. While you are having all of these thoughts you are distracted from the task at hand and your concentration and working memory suffer.

Does it always happen? No. There is only one prerequisite for stereotype threat to happen: the person in question must care about the performance in question. The fear of confirming the negative stereotype then becomes upsetting enough to interfere with performance. It is now known that stereotype has the strongest negative impact when people are highly motivated and performing at the frontier of their skills.

Solutions: bridging performance gaps through small interventions

Can something be done about it? Yes. The promising news is that there are some rather small interventions which can help a lot. Experiments have shown that subtly removing or preventing stereotype threats can completely or largely eliminate performance gaps between stereotyped groups and non-stereotyped groups.

Examples of helpful interventions are:

- Make it clear in the way you give critical feedback that you use high standards and let the person know that you expect him or her to be able to eventually succeed.

- Improve the number of people from the social category in the setting so that a critical mass is reached.

- Make it clear that you value diversity.

- Foster inter-group conversations and frame these as a learning experience.

- Allow the stereotyped individuals to use self-affirmations.

- Help the stereotyped individuals to develop a narrative about the setting that explains their frustrations while projecting positive engagement and success in the setting.

Conclusion

The tone of the book is informal, friendly, and personal, and the content is profound. The topic is highly relevant both to the development of social psychology and to the development of our educational systems and societies at large. Of course it also can inspire positive psychology research: how have certain individuals managed to overcome stereotype threat, how do certain organizations manage to bridge performance gaps, how do societies manage to do the same?

References

- Steele, C.M. (2010). Whistling Vivaldi: And Other Clues to How Stereotypes Affect Us (Issues of Our Time). New York, W.W. Norton & Company.

- Steele, C.M. & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69, 797-811

* I am especially in awe of the work Steele has done in collaboration with Joshua Aronson, who is now an eminent professor at New York University.

Friday, April 2, 2010

Self-Determination Theory Meets Solution-Focused Change: Autonomy, Competence and Relatedness Support in Action

By Coert Visser

This article looks at the Solution-Focused approach (SF) through a Self-Determination Theory (SDT) lens. SDT is an influential macro theory of human motivation which has been applied to many life domains, including sports, education, psychotherapy and work. The theory focuses mainly on the benefits of self-determined behaviour and the conditions that promote it. Its relevance for helping professionals such as psychotherapists and counsellors has been recognized by previous authors. A counselling approach which has been associated with SDT is motivational interviewing (MI). This approach has some important similarities to SF but there are also some key differences. This article focuses on the relevance of SDT for SF and vice versa. Although the literature on SF makes only a few mentions of SDT, SF fits well with its main propositions and findings. The strategies, principles and interventions of SF have the effect of supporting the perception of autonomy, competence and relatedness of clients which, according to SDT, are keys to enhance self-determination. It is argued that the SDT framework and body of research are relevant for SF. They help to understand better how SF works and may be used to further refine and develop the approach. In the same way, SDT theorists and practitioners may benefit from learning about the specific and often subtle ways in which SF supports clients’ autonomy.

Full reference to the article: Visser, C.F. (2010). Self-Determination Theory Meets Solution-Focused Change: Autonomy, Competence and Relatedness Support In Action, InterAction - The Journal of Solution Focus in Organisations, Volume 2, Number 1, May 2010 , pp. 7-26(20)

Full reference to the article: Visser, C.F. (2010). Self-Determination Theory Meets Solution-Focused Change: Autonomy, Competence and Relatedness Support In Action, InterAction - The Journal of Solution Focus in Organisations, Volume 2, Number 1, May 2010 , pp. 7-26(20)

Read the full article »

Monday, March 1, 2010

How Equality Drives Thriving

Coert Visser, 2010

The Relationship between Equality and Thriving

The Relationship between Equality and Thriving

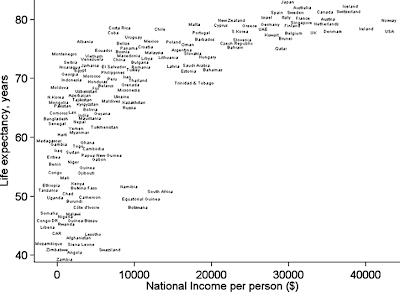

Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, two English epidemiologists, have written The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger , a provocative book on how high levels of inequality in societies is harmful for everyone within them. Their research shows that while economic policies in developed countries stress the importance of economic growth, economic growth is mainly an important determinant of the degree to which societies thrive. After a certain point the contribution of further economic growth begins to create only diminishing marginal returns: the relationship between economic growth and certain objectively measurable outcomes, like life expectancy, level off (see figure 1).

, a provocative book on how high levels of inequality in societies is harmful for everyone within them. Their research shows that while economic policies in developed countries stress the importance of economic growth, economic growth is mainly an important determinant of the degree to which societies thrive. After a certain point the contribution of further economic growth begins to create only diminishing marginal returns: the relationship between economic growth and certain objectively measurable outcomes, like life expectancy, level off (see figure 1).

Source: Wilkinson & Pickett, The Spirit Level (2009)

In developed countries, national income per person and economic growth are not the most important predictors of societal thriving but the level of equality. Wilkinson and Pickett’s research shows that many health-related and social problems are associated with the level of inequality of society. Here is how they did their research. They gathered data from 23 of the richest countries in the world from the World Bank and gathered internationally comparable data on the following health and social problems: level of trust, mental illness (including drug and alcohol addiction), life expectancy and infant mortality, obesity, children’s educational performance, teenage births, homicides, imprisonment rates, and social mobility. Here is an example of a graph, showing how an index of these measures is related to income inequality.

Source: Wilkinson & Pickett, The Spirit Level (2009)

To test and cross-validate their findings, the researchers tested these findings in a new data sample which consisted of the 50 American states. This research confirmed their findings across nations which adds to the credibility of the claims. Below is a graph showing how the index of health and social problems is related to income inequality in US States.

Source: Wilkinson & Pickett, The Spirit Level (2009)

The book contains many more graphs showing specific relationships between income inequality and separate measures of societal functioning (see these slides).

Why is this relevant for positive psychology?

Positive psychologists have done much research into how money is associated with happiness and some of their findings, at first glance, seem to be at odds with Wilkinson and Pickett’s findings. Berg and Veenhoven (2010), for instance, found little relationship between income inequality and average happiness in nations. It seems paradoxical that income equality would be related to many objectively measurable problems but hardly at all with happiness. How can one be equally happy when objectively things are worse? What is going on here?

This question takes us back to the original formulation of positive psychology’s mission. Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (2000) wrote: “We believe that a psychology of positive human functioning will arise that achieves a scientific understanding and effective interventions to build thriving in individuals, families, and communities.” This wonderful definition allows for research to identify any type of determinant of thriving to be found, like personal, motivational, habitual, or situational.

In practice, however, positive psychology is usually more narrowly operationalized. For instance, on the Wikipedia page of February 15, 2010, it is defined as follows: “Positive psychology is a recent branch of psychology that studies the strengths and virtues that enable individuals and communities to thrive”. This definition mentions only strengths and virtues as candidates for causal factors of thriving and it makes no mention at all of contextual, situational or structural factors affecting thriving.

A broader perspective on thriving and its determinants

As psychologists, we have known for a long time how important situational factors are in influencing our perceptions, beliefs, behaviors, feelings, and performance. Wilkinson and Pickett’s research is another example of this and it fits splendidly within the original definition of positive psychology in the sense that it contributes to the scientific understanding of how communities and its members thrive.

Also, it is an illustration of the limitations of using subjective criterion measures in research. Apparently, we can report well-being while objectively things are not going too well, both on an individual level and on a society level. We should not equate thriving or flourishing with subjective well-being. On this Barbara Fredrickson, author of Positivity, writes: “Flourishing goes beyond happiness, or satisfaction with life. True, people who flourish are happy. But that's not the half of it. Beyond feeling good, they're also doing good -adding value to the world. People who flourish are highly engaged with their families, work, and communities. They're driven by a sense of purpose: they know why they get up in the morning.’

For positive psychology to thrive, it needs to move beyond a somewhat narrow focus on happiness and strengths and take into account a broader perspective on thriving and its determinants.

References

- Berg, M. & Veenhoven, R. (2010). Income inequality and happiness in 119 nations. In search for an optimum that does not appear to exist. In: BentGreve (Ed.) ‘Social Policy and Happiness in Europe’, Edgar Elgar (in press)

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2009). Positivity. Groundbreaking Research Reveals How to Embrace the Hidden Strength of Positive Emotions, Overcome Negativity, and Thrive. New York: Crown Publishers.

- Pickett, K. (2010). Why Inequality is bad for your health. http://bigthink.com/ideas/18463

- Seligman, M.E.P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive Psychology. An Introduction. American Psychologist. Vol 55. No. 1. 5 14

- Wilkinson, R. & Pickett, K. (2009). The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger

. New York, Bloomsbury Press.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)